Codepraxis, the PMP coding app, will soon be launching in partnership with the Maine Correctional Center following a lengthy, tortuous process of trial, error, and retrial. What follows is an abridged retelling of the process straight from the people involved in its development.

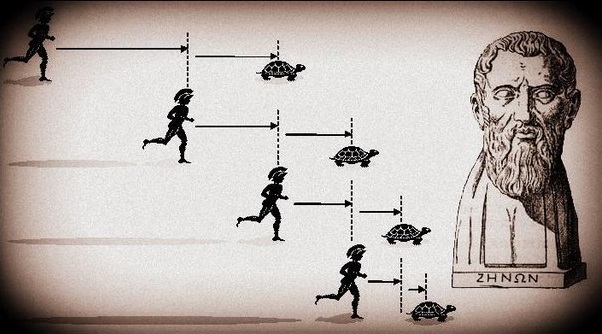

Christopher Havens: I remember quite a few years back, I was studying the theory of computation under our organization's advisor, my friend, Prof. Amit Sahai of UCLA.

Amit Sahai: It was wonderful seeing Christopher tackle a new area of mathematics, the theory of computation. He worked very hard to understand the theory of finite state machines and progressed to a level of mastery. But when we got to Turing Machines and general-purpose programming, things got a lot slower.

CH: The limitation was my foundations. It sure would have gone a long way to have some experience in algorithms and in programming, which is basically a process for devising and then implementing certain algorithms. I did fairly well under Amit's guidance, but there was always a gap in my understanding around constructing algorithms, which affected my ability to build Turing machines for various purposes. In the study of computation theory, this was important, and I felt it.

AS: At this point, it became clear to me that Christopher really needed to get a “feel” for programming with direct experience. I asked Christopher if there was any way he could get his hands on a laptop, and I found a beautiful introductory book on a programming language called JavaScript, which is always pre-loaded into any laptop because it is necessary for loading web pages. Christopher told me that getting a laptop would be tricky.

CH: But all of a sudden, it was like my needs were answered! There was a web development course, which included a whole quarter on basic JavaScript. This was more than I could hope for. And I was lucky because even though I had too much time on my sentence to enroll in the class without a special override from DOC headquarters, my involvement in mathematics helped my case, so I was enrolled! The course would come with a laptop that I would be allowed to use in my own room, even on my off hours. I could finally learn the necessary algorithmic thinking through real experience in programming.

AS: I was thrilled! I sent Christopher the book, called Eloquent JavaScript, and he started to devour it.

CH: After I started the course, I focused on JavaScript. I was learning on my own, as well as in classes, so I was ahead of my fellow classmates. But it wasn’t long until our computers were taken for a routine security check, where we turned them in, and about four days later, we received them once again. That little interruption, while it may not seem like a lot, would have been enough to break my stride, had I spent only classroom time learning programming. In your first steps in programming, it is easy to lose progress if you do not stick with it.

AS: Christopher would share his successes with programming with me regularly by email, and so I felt Christopher’s sense of loss when his laptop was taken just briefly. It was at this point that I started thinking: what should we do if the laptop is taken away permanently?

CH: After the first security check, we were able to continue once I got the laptop back, and so I plunged myself back into programming. Within a month, I was solving problems for my own research needs, and I was even able to obtain a LaTeX compiler. However, this did not last long. The next time we had to turn in our computers, we did not get them back for four months. All the skills I was learning began fading from my grasp, and I suddenly felt that the enormous effort I put in was for nothing...

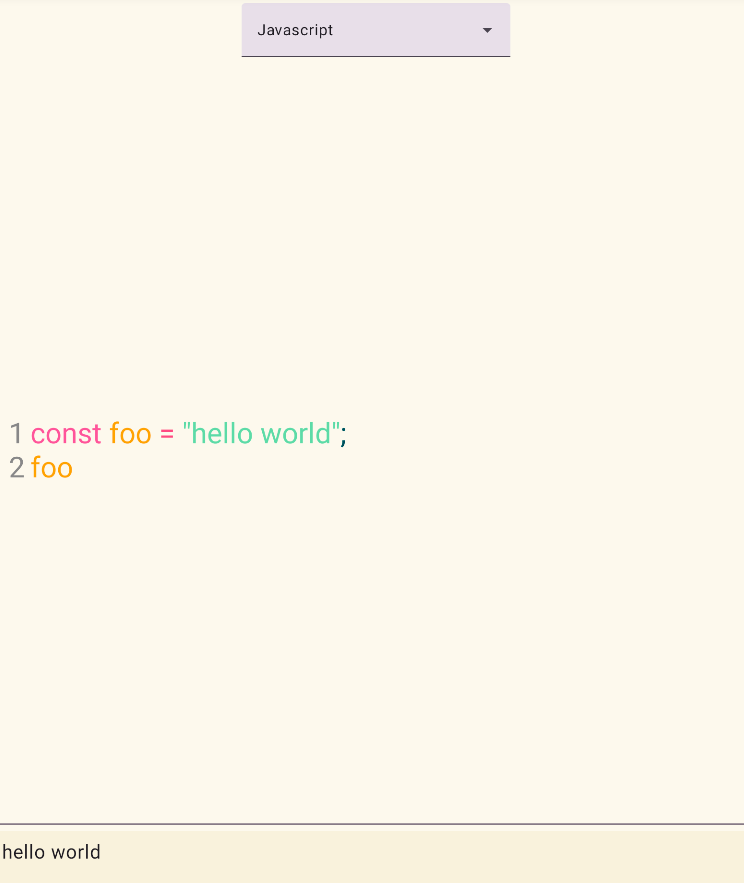

AS: Soon after Christopher’s laptop vanished the second time, I found a convenient web-based JavaScript programming environment that I could use anywhere. I talked with Christopher, and we decided that his programming education would continue, with or without a computer.

CH: Amit began sending me problems, and on top of that, I had personal programming goals that would assist me in mathematical research. Our idea was to send Amit the code, and he would then copy/paste my programs and run them. Afterwards, he would send me the compiled output in a message through the prison email system.

AS: I wanted Christopher to get feedback as quickly as possible, but of course, I didn’t always have time to spend on the code. So, I decided that whenever I had a few seconds, if I saw an email from Christopher, I would copy/paste it, and even if his program didn’t work, I would copy/paste whatever error code I got and just send it back immediately, so that the whole process took me seconds. I could do it mindlessly in the middle of working on my own mathematics, or during a brief break from talking with my family, without losing my train of thought.

CH: These exchanges took roughly 5 minutes each, due to the limited number of allowable email syncs within a given amount of time. This limitation was unfortunate, but it did have its benefits. A programmer might search out a bug by adjusting their code and hitting enter, and repeating as many times as possible until the program behaves correctly. In our learning process, I had to imagine the mechanics within my own algorithmic thinking before hitting the send button. In every five minutes before I could send a new query, I had time to visualize each step of the programming and, more often than not, to find flaws and to correct the bugs before I had the opportunity to even execute my code.

AS: The process worked surprisingly well on both our ends. When I had time, I would also send back some advice or even debug faulty code a little bit. It was clear to both of us that we had struck upon a really good idea – something that should be automated, and if possible, incorporated into a mentoring program where a mentor could also see the programs and output, and provide feedback and advice from time to time.

CH: This was where Cody Duncan became involved. He agreed to help with the automation process, and it became a system so powerful that I completely learned Python through Cody’s automation of our process for teaching programming!

AS: And thus, the PMP Console was born!

CH: The languages were referred to as NoTech JavaScript, and then shortly thereafter, NoTech Python. Since my technology limitations icluded not having the necessary symbols to program in either language, we had to use special symbols in their place. No white spaces, no ampersand, and no semicolons. So, the NoTech versions were the same, except some symbols were used differently. The automation was wonderful! The biggest problem was that it was expensive, as the cost of every transaction was 20 cents (10 cents each direction). I continued on my own because Cody and I were trying to expand the system and debug, and so I spent most of the time programming in the PMP Console. This seemed like the perfect solution for the problem of computer access in prisons, but the only way to do this would be to create an app, which could work on our tablets, rendering actual computers in prison 100% obsolete for the purposes of programming.

AS: It was amazing to see. Christopher would send me some of the programs he was developing with Cody’s prototype system, and with the automated system replacing my sporadic availability, he was progressing at warp speed! But then, after a few weeks, the powers that be decided that sending “computer code” qualified as sending prohibited “coded” communications. We tried to appeal this senseless decision, which was the result of an unfortunate quirk of history and language from the time when people had to manually “encode” their programming instructions into 0s and 1s for computers to understand. Unfortunately, our appeals fell on deaf ears. At this point, Christopher could no longer benefit from the fantastic system that he co-invented. But he knew that not all agencies would reach the same irrational decision, and even if he couldn’t personally benefit from PMP Console, maybe others could.

CH: I couldn’t help anymore with debugging the system myself, but it was clear that it was time to take the next steps. This is all history, really, and so I will let Ben bring you into our current state.

Ben Jeffers: After the initial console was shut down, we needed to pivot to something that was more cost-effective for our participants and could be more widely available. Lots of ideas were thrown around: whitelisting a website that has an online text editor and compiler, partnering with a company that made an IDE (integrated development environment), or even buying computers and bringing them into prisons. All of these had a clear fault: too narrow, too difficult, or too expensive. After taking a deep dive into the different organizations and universities teaching computer science in prisons, we noticed one big problem: a small percentage of people would sign up for a semester-long course, get access to a computer, learn a lot, and then never see a computer again until their release.

With the rise of tablets in US prisons, we thought that even though these companies are predatory, we could still make use of this tool to provide more high-quality education to more people. Since COVID, most people in state and federal prisons are given a tablet when they get to prison. On these tablets, they can buy movies, games, music, etc. We thought, why not put a coding app on the tablets? This would solve the problem of inconsistent access and would make it available to anyone who was interested, even those who could not qualify for a college course.

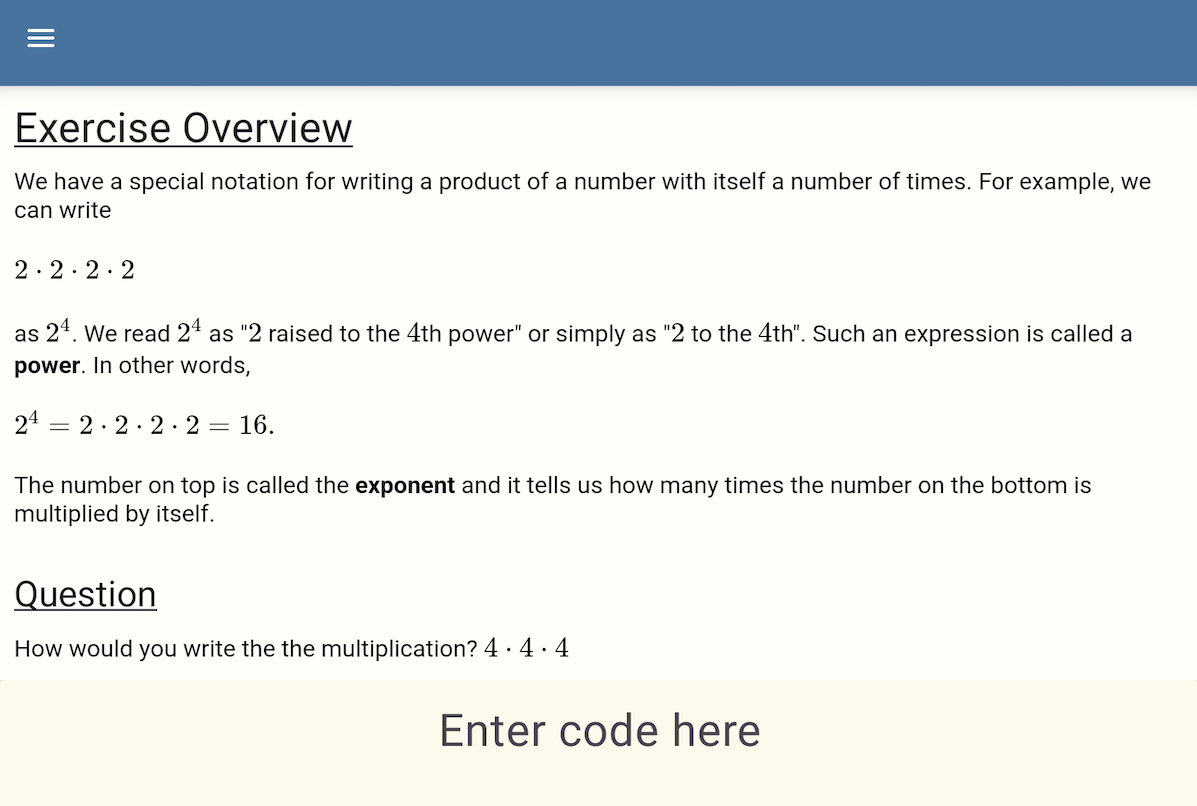

I pitched the idea to Christopher, and he was on board. Our developer, Cody Duncan, acted super quickly and had a working version in a couple of weeks. He built a text editor and compiler that can handle Python, JavaScript, and LaTeX. We can also upload courses with questions to be answered and verified.

The entire app is hosted completely on the tablet, no cloud, no external communication. This stripped-down approach should ensure that the security risks are nonexistent. The technical development turned out to be the easiest part. The Department of Corrections turned out to be the real challenge.

In the first round of discussions, no one would even entertain the idea of the app because it's “too dangerous.” One dismissal turned into another, which turned into a year of no progress. We started to lose hope and turn our focus back to our other programming, when we finally had our first glimmer of a chance. I received an email from one of the mentors in Australia connecting me to a friend who has been leading math circles for kids for many years (I had started to push for more in-prison programming based on math circles for kids). At the end of our chat, I mentioned our coding project and she introduced me to a friend who had previously worked for a large prison company in Australia.

I logged onto the Zoom meeting with him expecting to be met with the same frustrating barriers as in the US. Nothing could have prepared me for his enthusiasm about the project and the need for it in Australia. We had finally found a home for the project, and after more discussions with the staff based in Australia, we agreed to pilot the app at their biggest prison, and the largest in the country, Clarence Correctional Center. They were very excited about the project and wanted to get it done as quickly as possible. This change of attitude was incredibly refreshing and a much needed change of pace from the flagrantly oppressive US prison system.

We jumped into adapting the app for their tablets. Their team wanted us to integrate directly with their course management system, Moodle. This turned out to be more difficult than we had anticipated. And over the course of working with them, we started to have to wait longer and longer between responses from the team, sometimes going months and multiple emails without a response. When we finally heard back from the Australian team, they suggested just rolling out the app without the coding and a basic numeracy course teaching things like decimals, fractions, exponents, etc. It turned out that we were just recreating Moodle, which was never going to work as well as the one they already had.

While disappointed, we were going to continue with the project, until I got put in touch with Marrisa Gaetz from Brave Behind Bars (BBB), an MIT-based non-profit that teaches computer science remotely in prisons. They also got their start during COVID and were able to set up remote synchronous classes in Maine and Massachusetts, and now Washington D.C. Marissa kindly connected me with the head of education at Maine Correctional Center, and we’re working on piloting the coding app. They see the need for the app. Many of their students who take coding classes ask them for more time on the computers, and our app will provide just that.

I had always heard that Maine was the best and most progressive prison system in the US. Seeing it firsthand has been quite impressive. Incarcerated people are treated as human beings there, and their education is the most heavily emphasized aspect of their time in prison. We’re incredibly excited to be piloting the app in Maine, and hopefully, this momentum will lead to more states adopting the app.