The Prison to PhD Pipeline: Reaching Out

Travis Cunningham is a researcher in mathematical physics, in the subfield of scattering resonances.

Imagine finding your passion in life and then being unable to discuss it with anyone who shares that passion. That's what the beginning of my math journey was like. After several years devoted to mathematics, I could see the transformation it was making in my life and the promise for a brighter future it gave me. I wanted to shout about my newfound love for the world to hear. I wanted to tell people about this secret I discovered—about the beauty and power of mathematics. I wanted community.

I felt I was making tremendous progress in my studies, but I had no reference point and no way to know whether my understanding of math was significant. I did know, however, that to really fulfill my potential, I'd need to reach outside of these walls as well. But I hesitated for a long time. I didn't feel I deserved the world yet. Nor did I think there was anyone who would accept me or care about the progress I made in mathematics. My perception of what the world thought of me was very poor.

Trying to teach myself math in prison was already a lofty goal. It took a lot of courage and a lot of trust in my intuition. Eventually, I built up the courage to take another risk and to put myself out there by reaching out to some professors.

I wasn't researching yet. I had just read and understood a lot of math. From calculus to linear and abstract algebra, to number theory, ordinary differential equations, probability theory, from real to complex and functional analysis, to topology and modern algebra, manifold theory and differential geometry, several different texts on partial differential equations, microlocal analysis and scattering theory... the list goes on and on. In retrospect, I realize that I could and should have chosen a field that interested me and started researching much earlier than I did, because I had been ready for a long time. But really, I didn't know where to begin. That's the role of teachers and mentors, and I knew that was the piece I was missing.

I had a few one-off issues of Math Horizons and the American Mathematical Monthly, and just wrote to a handful of people whose addresses were listed in the journals. I introduced myself, described my interest in mathematics, the progress I'd made, and the goals I hoped to achieve. I just asked for any advice they had to offer. I really didn't expect a response, but I was hopeful. Much to my surprise, I received several responses. This was the first instance of many in which I have been blown away by the acceptance I've received from the mathematical community.

Although no one committed to any sort of mentorship, many offered bits of encouragement, advice, and one person even offered to send me textbooks. The consensus was clear: I should try my hand at research. One person put it bluntly: "I'm going to be real with you: if you want to take this to the next level, it is not enough to read and understand mathematics. Nobody cares about that. You must be able to do something of your own with it." I've always loved that sort of tough, real advice, and it immediately resonated with me. In addition, given my interest in partial differential equations and scattering theory, he suggested a then-recent monograph, "The Mathematical Theory of Scattering Resonances" by Semyon Dyatlov and Maciej Zworski. This is the monograph that introduced me to the field to which I have devoted the past 6 years of my life.

I took the advice I'd received and dove back into the isolation of my studies, but with renewed vigor, finally trying to do something of my own with mathematics. I devoured the monograph suggested to me and fell in love with it. The text read differently than anything I'd studied previously, and I was infatuated, mesmerized by the deep interplay between physics and mathematics. Not since studying that first calculus textbook had anything felt so right and excited me so thoroughly.

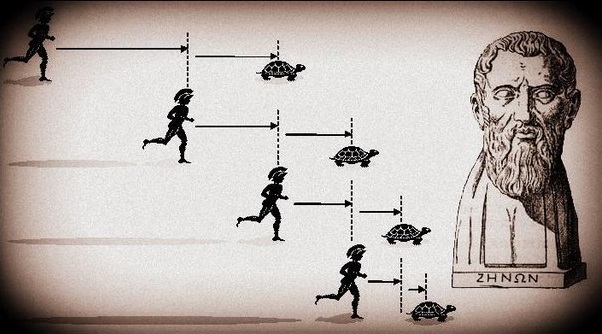

The open problems discussed by the authors dominated my thoughts. I was struck by the fact that explicit asymptotics for the resonance counting function are known in dimension one, showing that there are infinitely many resonances for any choice of potential. Yet only an optimal upper bound is known for higher dimensions. Moreover, an entire section of the monograph is devoted to a result of Tanya Christiansen (who would become my mentor), which showed that an analogous asymptotic CAN'T hold for all potentials in higher dimensions, since she proved the surprising fact that there exist Schrödinger operators having no resonances at all! Her result is a perfect example of the complicated, astonishing, and varied nature of resonances. Sometimes they behave very similarly to eigenvalues for closed systems, appearing in the expansions of waves, and exhibiting precise asymptotics similar to a Weyl law. Sometimes there is almost no correlation at all. These facts, elegantly reiterated throughout the monograph by Dyatlov and Zworski, inspired me to start trying to create, rather than just understand. And some ideas began to form that would eventually lead to my first published paper. That one leap to reach out for help had already sparked so much.

Shortly after reaching outside these walls for the first time, I received another issue of Math Horizons. I was surprised to find a story about the Prison Mathematics Project holding a "Pi Day" celebration at a Washington state prison to disseminate the study of mathematics to those incarcerated. Not only were the people I'd initially reached out to so kind and accepting of someone in my position, but here was an entire organization of people willing to volunteer their time to spread mathematics to people in prison. I had to get involved. So, I wrote the PMP a letter to introduce myself and began building the community I had craved. The PMP showed me immediate kindness, acceptance, and understanding. They even arranged to hold several Pi Day celebrations at my facility. This allowed me to finally talk about my passion face-to-face with other mathematicians. But the most important thing they did for me personally was to provide a crucial push, urging me to once again reach out for help—this time, to the top researchers in my field, who would become my mentors and take my research ability to a level otherwise unattainable.

Header photo by the blowup on Unsplash.