The Prison to PhD Pipeline: How?

Travis Cunningham is a researcher in mathematical physics, in the subfield of scattering resonances.

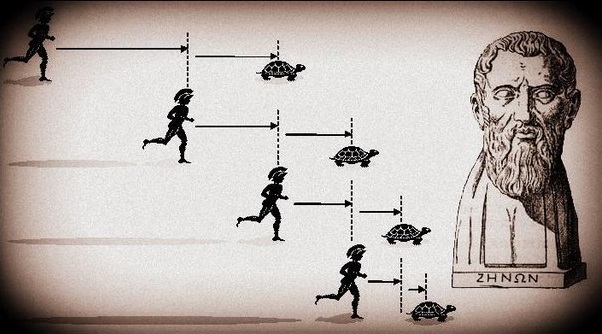

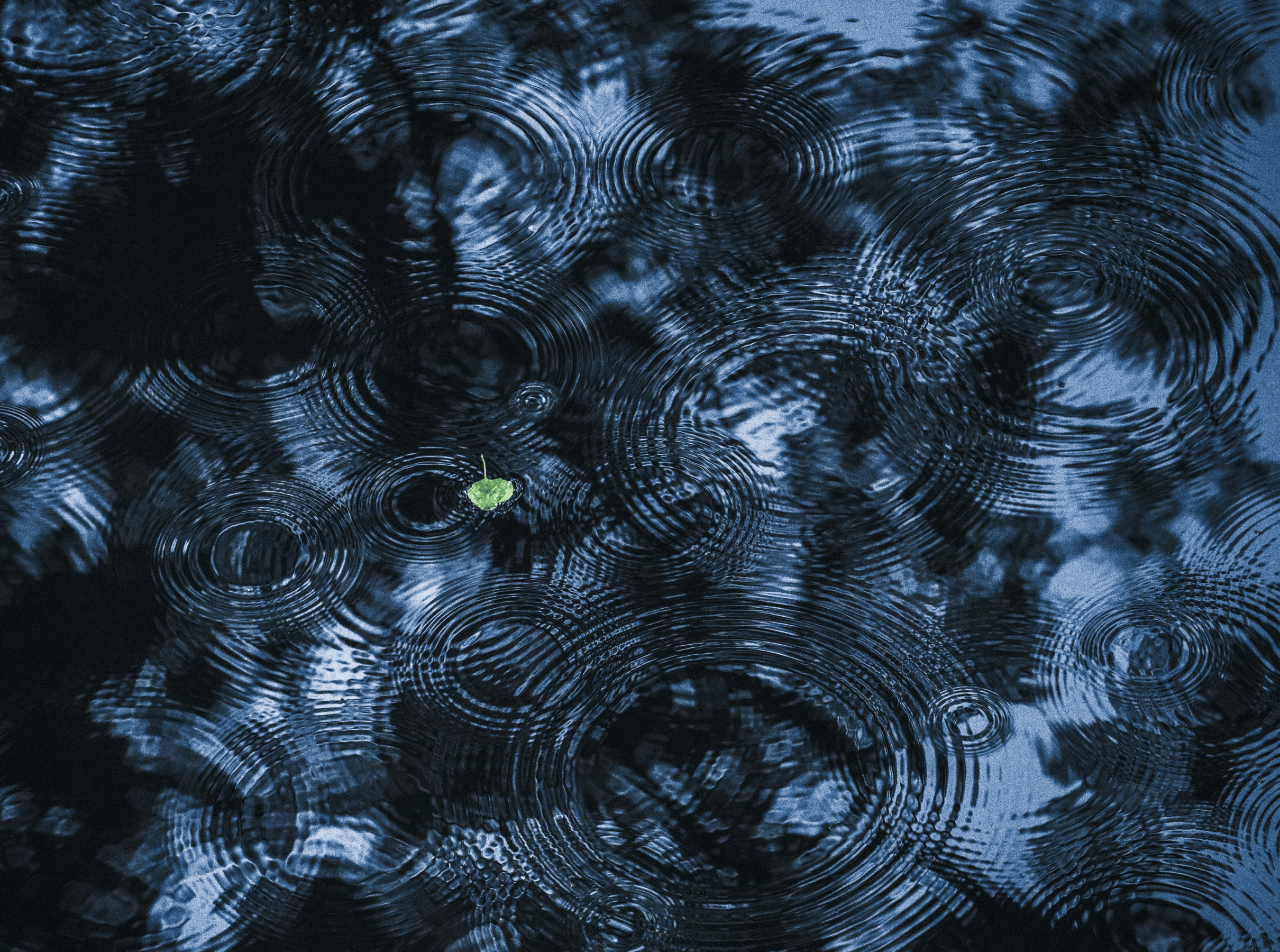

Awake in the middle of the night, angling my book to catch what little light streamed in from the cell window… I can't sleep, not until I understand the expansion of scattered waves in terms of resonances. The brief joy might be enough to dampen the dark thoughts and last until I drift to sleep. Trying not to wake my cellmate, wondering if I'll ever sleep that well again… We write the solution in terms of the spectral measure, then… no. Then introduce the resolvent via Stone’s formula... A contour integral… Ah, YES to extract resonances! Then,a remainder bound, not quite exact like an eigenvalue expansion. Decay due to imaginary parts of resonances... beautiful, like we can see the physics. I close the text, then my eyes, and see ripples on a pond slowly dissipating as I fall asleep.

...

I draw a lot of inspiration from the story of Srinivasa Ramanujan. Many of you already know it: Born in a small town in India, he had no formal math training but rather taught himself with minimal resources. After reaching out to researchers at Cambridge University, Ramanujan began publishing work with his mentor G. H. Hardy. I remember reading his story early in my sentence, and the way mathematics seemed to pluck him out of obscurity and offer him her hand resonated with me. It seemed he was destined for mathematics, almost chosen by it—a calling he didn’t deny as he subsequently gave himself over to it and relentlessly, obsessively pursued his passion.

I also remember being appalled years later when I saw an episode of Ancient Aliens on the History Channel, which reduced his story to some comments he made about the goddess Namagiri writing equations on his mind. The episode made it seem as though he had claimed that all his mathematical ability came to him in dreams, handed to him by the deity. Instead, Ramanujan worked obsessively, persevering through sickness and hardship. He overcame a tremendous lack of resources in the pursuit of his passion. Regardless of the truth of his claims about Namagiri, the Ancient Aliens episode neglected the hours and days and years of passionate study and work. It neglected all the details like running out of paper and writing in different color ink on paper he had already used, or the way he would come to his results intuitively, but then test them computationally with hundreds of examples and tweak them when necessary. In short, it neglected his process.

I work with every ounce of my being to make an impact with my research, but what I secretly hope for above all is that my story might inspire someone like me to believe in themselves and go for it, no matter how much of an uphill battle it seems.

I'm extremely proud of my tangible achievements, namely a publication and the writing of several other papers on the way. I also recognize that being self-taught and in prison adds some intrigue to these facts. But the reality is that my research alone is one small part of my story. Any mathematician will tell you that a research paper is a tiny fraction of the work that goes into it. There are twists and turns, false starts, dead-end rabbit holes… days and days of discussion, pages and pages of notes, countless papers read that end up not helping at all. And don't even get me started on the dreaded detail check, when you think you have a sound proof of some crucial theorem, but find a subtle error that makes the whole thing unravel. All you can do is roll up your sleeves and either fix it or find another way (most often only after a long, dramatic walk listening to Band of Horses). Some of my best work is lost in technical lemmas that never led to major theorems because some complementary piece couldn't be proved. Although it's all the world gets to see, my published paper isn't just three main theorems, a handful of technical lemmas, and an appendix. It represents a two-year journey in which I learned more about myself than in the whole rest of my life combined.

In the same way, although I was highly motivated (as described in my last post), the actual learning of mathematics is a lot more complicated than just spending time reading textbooks, especially in this environment. It was a winding path filled with doubt and setbacks, an endless stream of obstacles to overcome, as well as the internal struggles I was facing. I think that is where my story has some value; it is why I've wanted to share it here. If somebody reads this and hangs on a little longer, perseveres a little harder, or goes after that "impossible" goal because I'm proof that it is possible, then that will make sharing my story worthwhile. I work with every ounce of my being to make an impact with my research, but what I secretly hope for above all is that my story might inspire someone like me to believe in themselves and go for it, no matter how much of an uphill battle it seems. That's exactly what Ramanujan's story did for me.

I wrote a bit about my "Why?" in the last post, and here I want to talk about how exactly I learned mathematics, including both some of the logistics and some of my favorite study techniques. That is, I want to talk about my process. Research is a different process entirely, and I'll write about that in future posts, but here I wanted to focus on my process for learning mathematics in the first place.

I mentioned in "A Spark in the Dark" that after studying a calculus textbook, I was sent several of MIT's free online resources. I don't have any direct access to the internet, so I couldn't look for such resources myself (I was not even sure such resources would exist). Instead, I mentioned to my father a desire to continue studying math, but that I didn't know where to turn next. He went online, found MIT's resources, and printed and mailed the material to me. Among these resources were their math and physics course numbers, descriptions with prerequisites, required textbooks, lecture notes, and their degree requirements. It's impossible to overstate the importance of receiving these materials. By the way, what a tremendous gift to the public! The decision to have this information online freely available to anyone, even someone incarcerated, genuinely changed my life. It described exactly what courses were required for an undergraduate degree in math, even giving sample undergraduate curricula, explaining that a certain number of courses from each major branch of mathematics (Analysis, Algebra, and Geometry) are required. Using this information, I was able to proceed with my studies in a structured way, with confidence that I was covering material useful for later, more complicated courses. The MIT online resources were essential in helping me construct a deep, well-rounded undergraduate level of mathematical ability.

If you want an excuse not to pursue your goals in prison, you'll find it.

Motivation, check. Logical plan of action, check. But now I had to actually understand the material in front of me. I couldn't ask anyone any questions. There was no one to explain particularly difficult parts or make sense of a proof, as I had not yet learned of the PMP. If I wanted to understand, I had to figure it out for myself. Early on, I wished I had someone to teach me. But in not having it as an option, I learned a sort of toughness in the way I approached my studies. There was no giving up and googling it, or asking a peer or a teacher for help. If I wanted to learn the concept and move on, I had to persevere and figure it out alone. I had to learn how to be my own teacher.

So, I developed several useful study techniques. Alas, I suspect these techniques are not novel, and perhaps they are taught to mathematics students at universities. But I had to discover them on my own.

The first is my favorite, and although surely I'm biased, I believe it to be the most effective way to learn math. Anticipation. It's a form of active reading in which one is constantly thinking ahead, on many different scales. What is the next line going to be? What's on the next page? What is all of this leading towards? I'd constantly be trying to complete the thoughts of the author. I would try to prove results without looking at the proofs or read just enough of a proof to get going, then fill in the rest of the details. It was a way to really squeeze every drop out of the only resource I had at the time, textbooks.

My next favorite study method is particularly helpful when the material is more difficult, or when I find myself unable to anticipate where the author is going next. I'd rapidly skim an entire section,chapter, or even the whole text. No details, no proofs, just quickly read ahead in order to get a glimpse of the "big picture." This is useful for two reasons. First, it is easier to anticipate when you know some of what's coming next. Secondly, and more importantly, it was a way to train mathematical intuition. By skimming mathematics, one does not really get any sort of real understanding of what is being read. To understand math, you really do need to go through every detail, read and re-read, pause to think, do problems, etc. But by skimming, one kind of wakes up all the subconscious processes by which we connect the dots in mathematics. I don't think anyone really knows why or how mathematical ideas or understanding come to them. I can study the same concept over and over, employing all my methods, and yet make no progress. Then, during a walk later, everything just clicks into place. But what I do know is that more of those types of moments, those little bursts of intuition and understanding, happen when I first skim the material before really studying it.

The final technique I want to describe is to look ahead. Unlike the skim of the rest of the chapter, I mean to look WAY ahead in research journals and monographs when one is still studying the basics. One cannot start reading research too early. From the very beginning, I started reading research journals and monographs at the end of study sessions(in my leisure time, as hysterical as that sounds). Of course, I couldn't understand it early on, but in my naivete, I tried, even though I only recognized bits and pieces. I found the mathematics beautiful and was amazed to find some of the concepts I was studying being used in such advanced material.It really motivates the study of an abstract concept, like the convergence of infinite series of functions, when you see it in use in a paper on the mathematics of gravitational waves. This "looking ahead" constantly reassured me that what I was pouring so much effort into would open the door to some very cool stuff, if I just kept at it. Yet another promise mathematics made to me. And kept.

Even with motivation, a plan, and an effective method of learning the material, prison has been a relentless obstacle. There are obviously no study halls, and it is rarely quiet. I live in an 8x10 ft cell with a bunk bed, a toilet, and a cellmate. I have experienced countless cell searches in which books are destroyed, pages of handwritten notes thrown about, torn up, or flushed down the toilet. I've had issues with mail in which textbooks or research papers are not delivered to me, with the staff citing some obscure facility policy, seemingly only to block me from receiving constructive material. I have had issues with other inmates, and I have been in solitary confinement, because no matter how hard you try, some conflict is unavoidable in here. If you want an excuse not to pursue your goals in prison, you'll find it.

So, I was intentional about never letting these things hold me back. In fact, every time something threatened my goals, I doubled down and worked that much harder. One constant I could always count on is that every night at 10 pm, the cell doors close for the night, the lights turn off, and for 8 hours, there is as close to peace and quiet as you're going to get. So, most nights, while the world around me slept, I worked. Awake in the middle of the night, angling my book to catch what little light streamed in from the cell window…

Header photo by ArtemSapegin on Unsplash